In front of me was a bookcase lined with the complete works of Samuel Beckett, some rare editions, placed above the complete recorded works of John Coltrane. Richard is a Pakeha or New Zealander of European descent, in his case Scandinavian, and yet he has been deemed and marked with a moko (tattoo) as a custodian of Māori culture.

In front of me was a bookcase lined with the complete works of Samuel Beckett, some rare editions, placed above the complete recorded works of John Coltrane. Richard is a Pakeha or New Zealander of European descent, in his case Scandinavian, and yet he has been deemed and marked with a moko (tattoo) as a custodian of Māori culture.

“Yes, and that is a huge and scary responsibility in many ways, and they have ways of marking you. Often I will have older people come to me and say ‘You will do this for the rest of your life’ — not a question but a command!

“You get taken up the coast and marked with a moko of the tuhonohono type. This two inch wide band around my upper arm. The teeth like pattern in the middle represents the ‘niho taniwha’ or teeth of the monster. In symbolic terms the ‘taniwha’ protected and guarded as well as ran riot.

“Generally the weaving pattern is regarded as a symbol of guardianship or protection and the opposition of the two sets of teeth, the gap or pathway through them, becomes ‘te ara puoro’ the pathway of music or sound. So it is the guardianship of music. It is a non-tribal tattoo, I’m not entitled to tribal markings. There is also a lot of this cross hatching (in tattooing) in Viking culture, which is my background. Same journey different route. The metaphor is always a journey, both public and private and I feel very privileged on a huge variety of levels.”

The pattern of his moko is also considered to be a representation of the barb of a stingray tail. Some weeks after being given his tattoo Richard was in the ocean, walking close to the shore, when he stepped on a basking stingray which left him a scar on his leg with its barbed tail.

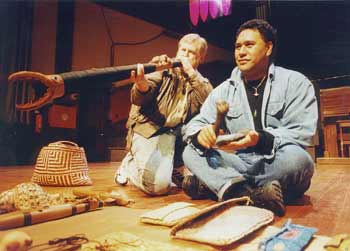

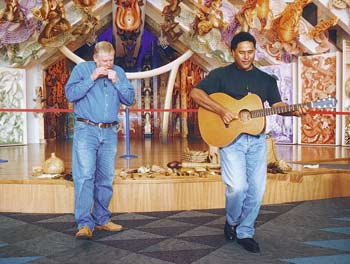

Much has changed in Richard’s life since I originally interviewed him. Back then he was a teacher of English language and literature at Nelson College for Girls from nine till nine. A lifelong career, or so he thought, until in his fifties he suddenly gave it up to pursue the music journey full time. Charged with returning any knowledge they were given access to back into the community Richard and Hirini travelled around giving workshops and concerts. From those particular situations they made no money.

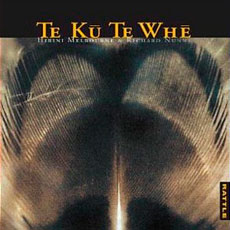

“As far as Te Ku Te Whe goes,…it’s sold quite a few thousand copies and any artist selling more than 500 copies of anything in New Zealand is big time!! So it’s nothing short of amazing and it just keeps rolling on, neither in nor out of fashion. I have little shame in talking about it because we don’t take any money out of it. The royalties get put into a trust fund at the moment, ultimately to build an endowment at Waikato University for post graduate study into traditional music.

“As far as Te Ku Te Whe goes,…it’s sold quite a few thousand copies and any artist selling more than 500 copies of anything in New Zealand is big time!! So it’s nothing short of amazing and it just keeps rolling on, neither in nor out of fashion. I have little shame in talking about it because we don’t take any money out of it. The royalties get put into a trust fund at the moment, ultimately to build an endowment at Waikato University for post graduate study into traditional music.

“Most of this knowledge that we have comes from the fragmented memories of very old women. There are, at the workshops, always young and old, right across the board. Our most comfortable place is always on the marae (a Māori meeting or gathering house) held in the arms of a traditional house in a traditional community where the traditional process can take place. It will then have its own time and it is usually, although not always exclusively, extended family taking part and you seed the knowledge. If we are doing anything at all it is simply alerting people to the fact that there is this extraordinary music that is here, belongs here and speaks of here in a most eloquent way.

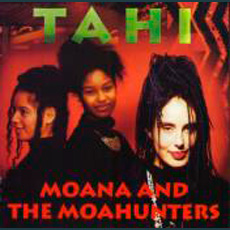

“When I play with Moana and The Moa Hunters she plays to audiences of between 10-14,000 people at times. So the instruments are out there in front of a lot of young disaffected Māori who have got their hats on backwards going ‘Yeoow man!’ and the whole black American cultural attitude. Whereas they have this extraordinarily rich culture here, and groups like Moana and The Moa Hunters are finding ways of taking that and placing it in a contemporary context that is entirely legitimate.

“When I play with Moana and The Moa Hunters she plays to audiences of between 10-14,000 people at times. So the instruments are out there in front of a lot of young disaffected Māori who have got their hats on backwards going ‘Yeoow man!’ and the whole black American cultural attitude. Whereas they have this extraordinarily rich culture here, and groups like Moana and The Moa Hunters are finding ways of taking that and placing it in a contemporary context that is entirely legitimate.

hugely steep. Not about learning to play the instruments, that’s a far more internal, organic thing that comes to me far more easily than, for instance, a notion that is held very high within the Māori community called ‘whakaiti’ or to make yourself humble; you do not stand up above the crowd, you do not poke your head up above others and they have extraordinary ways of levelling you back again if you do. If you want to learn about Māori things you do not ask. You go around the back and get invited in. You can semi-invite yourself by working in the kitchen, for instance, peeling potatoes. You don’t go around to the front and no matter how sensitive or how interested you might be they actually have no reason to give you any information at all. They have had 150 years of absolutely being screwed over by a colonial juggernaught and it’s still rolling, but they are rising out of that and it’s, as always, awkward and prickly, but thing are happening. There is a dynamic dialogue going on.

“I sometimes get challenged. There is now, of course, a new generation of young ones who don’t know the genealogy of who started this whole revival. Essentially myself, Hirini Melbourne and Brian Flintoff, the instrument maker. They just want to know ‘Hey, what’s this Pakeha doing with our instruments?’ But you leave it to others to explain what’s going on and often no amount of talk will explain anything anyway, so I just trust to what I can do with the instruments. That inevitably turns things around within a matter of seconds. They recognise that (for whatever reason, and I use the words very carefully) that I have been ‘gifted’ with a tradition and I am a conduit, a medium or a funnel. I can’t explain it myself, but that’s the way it is.

“I sometimes get challenged. There is now, of course, a new generation of young ones who don’t know the genealogy of who started this whole revival. Essentially myself, Hirini Melbourne and Brian Flintoff, the instrument maker. They just want to know ‘Hey, what’s this Pakeha doing with our instruments?’ But you leave it to others to explain what’s going on and often no amount of talk will explain anything anyway, so I just trust to what I can do with the instruments. That inevitably turns things around within a matter of seconds. They recognise that (for whatever reason, and I use the words very carefully) that I have been ‘gifted’ with a tradition and I am a conduit, a medium or a funnel. I can’t explain it myself, but that’s the way it is.

How did this happen? “You can live within and amidst another culture, anywhere in the world, and yet make no contact whatsoever. Parallel lines with no interconnection in any way. It wasn’t until my late twenties, when I was teaching at Waikato, that I became involved in the building of a marae (meeting house). Building the marae put me in touch with the Māori community. It led to what might be called a Marxist consciousness raising, or whatever you like. Over the period of a year building this marae I began to realise that there was another way of living in this country that I knew nothing about and which I found quite attractive. I asked some questions about traditional instruments, to which there was no response. Direct questioning within the culture is not productive and fortunately I knew enough not to pursue it.

“Moving down here to Nelson I became involved with bone carver Brian Flintoff, who was also very keen on making functional items and we slowly got our heads together. As well as the person to make them we are very blessed at the top end of the island here with the materials we need to make the instruments. There is a river outside the window there which provides us with greenstone jade, plus the bush up there where we get all the bindings we need plus some of the wood. Our relationship with the Department of Conservation is such that we get can get permits for bird bone, whale bone and teeth, seal skins, all that kind of thing. Our credentials are well established. There is no ‘take’ of endangered species, it is only when one is found or killed that it gets apportioned and it seems to have a way of coming when we need it.

“Added to the whole musical childhood and things with brass bands and my father, who was into big band music and a very good trumpet player and performer, it has become a relationship which continues very purposefully today. He is the design engineer and I’m the test pilot. Brian is not a musician but he has created some 90 instruments for me.

“About two years after we met we then met Hirini Melbourne who was thinking similar things about traditional instruments himself. The three of us have been working for over 25 years, travelling widely, researching, playing, taking knowledge back to people, back to roots, teaching and very successfully re-kindling interest in something which has been hidden for over 100 years.”

Michael and Richard collaborated on Cineclub Detour

“There are other makers now, a whole second generation, but they are very difficult instruments to play. You have to dredge from within you virtually eighty percent of the voice, sound and music from a little cylinder with three finger holes. It doesn’t automatically give you very much at all. You are literally dredging for music – a lifetimes work! “